Table of Contents

Hearing the Past : A virtual immersive audio concert for the ears

For functional translations, please use translator options or plug-ins in your web browser. Google page translations work for text, but without audio player functionaliy.

Recreating Notre-Dame Cathedral’s 850th anniversary performance of « La Vierge »

In honour of the International Year of Sound (sound2020.org) and for the 1 year memorial of the Notre-Dame cathedral fire, a team of researchers and sound engineers has recreated a virtual reconstruction of a recent performance recording made in the cathedral, recreating the monumental acoustics and the event.

As part of the celebrations of the 850 year anniversary of the construction of Notre-Dame de Paris, on 24-April-2013 the Cathedral welcomed a performance of La Vierge. Under the direction of Patrick Fourniller, this performance was recorded in detail by the Conservatoire de Paris (CNSMDP).

To share this performance with those who could not attend, and to honor the Cathedral, damaged by the fire one year ago, acoustic researchers and sound engineers have taken these recordings and an acoustical 3d model of Notre-Dame, created from measurements on the night of the concert (developed at LAM-IJLRDA, Sorbonne Université), to recreate the concert from several listening positions, offering a unique 3d-audio experience approaching the reality of the moment in the past.

This effort has been made possible by a grant from the CNRS Mission for Cross-disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Initiatives (MITI) and the Acoustic & Soundscape task force of scientists, “Chantier CNRS Notre-Dame”. Many thanks to the performers, musicians, and all those who made this possible.

Listen to the Concert

The audio is available for listening on-line using binaural audio technology (intended for headphone listening).

While this recent production is destined to provide an immersive realistic reconstruction of the concert, it is also possible to hear the full binaural artistic production mix of the concert made from these same recordings by the CNSMDP. This earlier production was made as many modern recordings, to present a high quality reproduction of the concert yet providing an unrealistic or physically impossible perspective of the musicians and the acoustic space. We invite you to compare the different approaches and the effect of position in the cathedral on the perceived acoustic.

As an introduction we present a montage of elements from the concert, available for different positions using the virtual acoustic reconstruction model, and the artistic production mix. To help us understand the appreciation of this effort, and to improve future productions, we would very much appreciate it if you could take a quick 5 min to respond to the following listener survey after the audio section on this site. All answers will remain totally anonymous.

Please note, this player is not compatible with IE. If you have difficulties in accessing the “play” button interfaces, please try to maximize your browser window or zoom out. There are also links (at the bottom of the player matrix) to the CNSMDP media site for each position if you prefer.

|  |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musical Piece | Rear audience seating position | Middle audience seating position | Front audience seating position | Conductor position | Artistic Mix (2013) |

| Montage for Survey (5:31) | |||||

We also present 4 different parts of the concert, accessible directly here, which we believe present interesting moments in the concert. For example, n°3 includes the children choir at the far end of the cathedral, n°10 includes the percussion section in the distance and the trumpets playing from the upper level of the transept, n°13 includes the same children's choir promenade near the audience, and n°15 is the finale, with the Soprano in the upper level of the transept at the applause of the public.

Finally, here is the entire concert, from each of these positions, which you can listen to at your leisure (wearing headphones of course).

| Musical Piece | Rear audience seating position | Middle audience seating position | Front audience seating position | Conductor position | Artistic Mix (2013) |

| n°3: Choeur des anges (6:23) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n°10: Le vendredi Saint à Jérusalem (11:01) | |||||

| n°13: Choeur des anges (10:48) | |||||

| n°15: L'Assomption (3:19) | |||||

| Full concert (1h23m) | |||||

| Links to advanced audio players | Rear position | Middle position | Front position | Conductiors position | Artistic mix |

Listening survey

Based on the production montages, we would very much like your opinion on this work. This should only take about 5 minutes of your time but will help us a lot in the future.

You can use the interface window below, or go to a separate page

The Acoustics of Notre-Dame

In Music History

For more than 850 years, Notre-Dame de Paris has been the sounding box for the city's sacred music. Built to amplify the sacred word spoken or sung, the Cathedral is a multiform sound space where the clamor of the pilgrims circulating in the ambulatory and the chanting of the services protected by the choir's enclosure, the soloist singing the mass and the humming of the low masses in the radiant chapels, used to coexist until today, when before the fire, the call to silence for noisy visitors, the sound of the masses, the bursts of sound from the great organs and the concerts alternated.

It should be noted that as soon as it was built at the end of the 12th century, the Gothic cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris became the emblematic place of musical creation in Europe, which historians call the “Ecole Notre Dame”. Documents testify to the musical activity during this period and it is possible to think that the spectacular development of this Parisian polyphony coincided with the organization of the liturgy in the new choir inaugurated in 1182: the decrees of Notre-Dame Cathedral, promulgated in 1198 and 1199 by Bishop Eudes de Sully, attest to a practice of two, three, and four voices for the responsorial chants of the mass and offices as well as for the Benedicamus Domino of Vespers[1]. Luckily we have the Treatise of Anonymous IV[2], written by an English schoolmaster, which describes the musical practices around 1275 in the choir of this Cathedral where the sound of the organum and semi-improvised conductus could rise, towards the apse, before being noted in various manuscripts which testify to the richness of the Magnus liber organi[3] (Latin for “Great Book of Organum” in use by the Parisian School of Notre Dame around the turn of the 12th & 13th centuries).

During the period known as Ars Antiqua, i.e. the transition period between the Ecole of Notre-Dame and Ars Nova (1320), the Cathedral gradually lost its musical supremacy as the clergy tried to maintain its high standards of musical quality by maintaining the eight children of the master's school and by financing the construction of the choir organs (circa 1334) and then the organ loft (circa 1415).

Over the centuries, the methods evolved and with the Gregorian melodies, which escape the closed choir or circulate with the processions, the sounds of the organ, the bells, and the complex polyphonic works of the Franco-Flemish counterpoint were mixed together. “The appointment of Antoine Brumel in 1498 brought a breath of fresh air: the future choirmaster of the Duke of Ferrara brought with him the best and latest in Franco-Flemish polyphony.”[4] The history of music will remember the names of great masters and composers such as André Campra, Jean-François Lalouette, or Jean-François Lesueur, who, after the revolutionary period, composed the famous March of the Coronation, for Napoleon's entry into the cathedral in 1804, and various pieces for the Coronation Mass. That was a great opportunity to hear the organ built by François-Henri Clicquot (1783), then restored again by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, while Viollet-le-Duc proceeded with the restoration of the building.

During the creation of La Vierge by Massenet, the chapel master Charles Vervoitte (1819-1884) restored the prestige of the music in the cathedral, the scene of the conversion of young Paul Claudel, a convinced atheist, to the Catholic faith by listening to Magnficat sung at Vespers on Christmas Day, 1886.

The vaults heard everything during the 20th century, starting with the concerts of the greatest French organists and the most diverse musical groups, not forgetting the songs of the liturgy. “In 1990, Cardinal Lustiger asked Jean-Michel Dieuaide to rethink the cathedral's permanent musical system. This reflection was carried out in collaboration with Guillaume Deslandres, who founded the association Musique Sacrée à Notre-Dame de Paris (MSNDP), of which he became the first director. (…). As in its early days, music continues to play a considerable part in the influence of Notre-Dame Cathedral. The weekly organ auditions, the monthly organ recitals, the concerts given by the Maîtrise (choir of the Cathedral), all testify to the high standards and excellence to which all those involved in music at Notre-Dame today apply”[5], suddenly interrupted by the silence following the fire and which new technologies could accompany in order to recover the very special acoustics of the Cathedral while awaiting its reconstruction.

- The main documents evoking this practice in organo, vel triplo vel quadruplo were published in 1932 by Jacques Handschin: Zur Geschichte Notre-Dame, Acta Musicologica, 4, 1932, pp. 6-14. See more recently Craig Wright, Music and Ceremony at Notre-Dame de Paris, 500-1500, Cambridge (Mass.), Cambridge University Press, 1989, pp. 239-243 and 369-370.

- Anonymous IV points to two instances of Perotin’s organum quadruplum – Sederunt principes and Viderunt omnes – in which the rhythmic swirling and interweaving of vocal parts make for a strikingly original sound-world. Experience Sederunt principes, yet another window into the medieval imagination, as performed by Organum ensemble. It was first performed in dedication to a new wing of Notre Dame Cathedral in 1199.

- Edward H. Rosner (ed.), Magnus liber organi de Notre-Dame de Paris. Les quadrupla et les tripla parisiens, vol. 1, Monaco, L’Oiseau-Lyre, 1993, p. XIX-XXV followed by other volumes.

- See L’école épiscopale.

- Idem.

Frédéric Billiet, Professeur en musique médiévale, Sorbonne Université

The Acoustics

Notre-Dame de Paris is among the most well-known worship spaces in the world. Its large volume, in combination with a relatively bare stone construction and marble floor, lead to rather long reverberation times.

The same day that recordings were made of the concert, the team also made detailed measurements of the cathedral's specific acoustics. These measurements helped to quantify the acoustic conditions in the cathedral, in 2015. As an example, the reverberation time, or the time is takes for a sound to decay by 60 dB (to inaudibility) was found to be as follows:

| 250 Hz | 500 Hz | 1000 Hz | 2000 Hz | 4000 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reverberation Time (sec) | 8.4 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 4.6 | 3.0 |

The full details of the measurement method, results, and comparisons with measurements made only a few decades earlier have been presented at a scientific conference, and can be consulted in this article : Acoustics of Notre-Dame cathedral de Paris

Massenet's "La Vierge"

Who is Massenet

Passed on to posterity for the meditation of Thaïs or the letters aria from Werther, the figure of Massenet (1842-1912) remains attached to that of the French opera before Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande. Massenet also cultivated the oratorio, as evidenced by Marie-Madeleine (1873), Eve (1875), La Vierge (1880), and La Terre promise (1900). The distance between opera and oratorio, between sacred and profane love, is tenuous at the end of the 19th century, which saw the birth of Franck's Les Beatitudes (1879) and Gounod's La Redemption (1882). It is therefore not surprising that Massenet's work was premiered at the Paris Opera on May 22, 1880, during the first of the Historical Concerts of the new director Vaucorbeil, alongside works by Lully, Rameau, Gluck, and Grétry in the first part.

A pupil of Ambroise Thomas, who won first Prix de Rome in 1863 and was appointed professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire in 1878, Massenet had made a name for himself with the orientalist opera Le Roi de Lahore (1877) when he tackled his oratorio La Vierge, a figure he would find again in the lyrical miracle Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame (1902).

La Vierge

In 1875, Massenet had met the young poet Charles Grandmougin who wrote for him the booklet of this sacred legend in four parts: The Annunciation, The Marriage at Cana, Good Friday, The Assumption. He completed his score on August 22, 1879. The four parts retrace four key moments in the life of the Virgin: the arrival of angel Gabriel announcing that she will give birth to a son, her incomprehension when Jesus seems to deny her during the wedding feast at Cana, the mother in tears at the foot of the Cross, and finally her ascent to Heaven, contrasting situations exploited by Massenet. More dramatic, but also shorter, the two central parts draw on the operatic side with grandiose choirs (no. 5: Chœur du festin), funerals (no. 10: “c'est Jésus qu'on mène au trépas”), but also moments of choral recitation (“Jésus s'est arrêté”) reminding of Berlioz's Roméo et Juliette ouverture. The two extremes would rather lean towards Berlioz's L'Enfance du Christ, with this initial, almost monodic Pastoral. The Fourth Part remains the one that our 21st-century sensibilities understand best: the instrumental Andante religioso (No. 10: “Last Sleep of the Virgin”) is taken up again in the Chœur des Anges with a wonderful harp accompaniment, while the ecstasy of La Vierge, “Infinite Dream, Divine Ecstasy,” literally transports the listener to the afterlife before the Magnificat closes the ensemble.

Lucie Kayas, Doctor in musicology, professor of musical culture at the CNSMDP

Review of the 24-April-2013 performance

Sacred legend in four scenes, for soloists, choirs & orchestra. Libretto by Charles Grandmougin. Norah Amsellem, soprano. Maitrise de Notre-Dame de Paris, French Army Choir, Sotto Voce Children's Choir. Orchestre du Conservatoire de Paris, dir. Patrick Fournillier.

Presented as part of the celebration of the 850th anniversary of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral, the Virgin, by Jules Massenet (1842-1912) is a rare work, first performed in 1880 at the Paris Opera, under the direction of the composer. At its premiere, initially scheduled at Notre-Dame, this work was highly regarded and received a rather cold reception, due to the heavy program, which presented works by many other composers together. The illustrious soprano Gabrielle Krauss could not, despite her talent, save this magnificent composition from the indifference of a tired audience, a selflessness of which Massenet will keep a painful memory for the rest of his life. Sacred legend in four scenes, from a text by Charles Grandmougin, evoking the main episodes of the Virgin's life through the biblical accounts of the Annunciation, the Wedding at Cana, Good Friday and the Assumption, this oratorio, with its terribly human accents in the expression of feelings, emancipates itself from the liturgy to become a true concert piece. One finds in it one of the great feminine figures of Massenet's imagination, with its joys, its rages, its weaknesses, its pain; which did not fail to provide subject to criticism, some reproaching Massenet for having composed too theatrical a music on such a mystical subject… A music, indeed, full of dramatic effects, colors, rhythm, different climates sometimes very surprising, like the very profane Galilean dance.

A brilliant work by its melodic line and the richness of its orchestration, grandiose and moving, served by a stage of more than 250 musicians, placed under the direction of Patrick Fournillier, undisputed specialist of the work of Jules Massenet, who leads from hand to hand, from end to end, with precision, commitment, and delicacy. Norah Amsellem, too often absent from the French stages, although she has had an international career for several years, knew how to give the Virgin all her humanity, through her remarkable singing, her perfect diction and her stage presence. Patrick Fournillier dedicated a very beautiful evening to Sir Colin Davis, another great specialist of French music, who recently passed away. A very nice tribute!

-Translation of Une œuvre rare, La Vierge de Jules Massenet, by Patrice Imbaud, June 2013

How it was done

The creation of this virtual concert reconstruction followed several stages : recording, acoustic simulation & auralization, mixing. Each of these elements is described briefly here. Links to more detailed presentations of each element are provided for the interested reader.

Concert recording

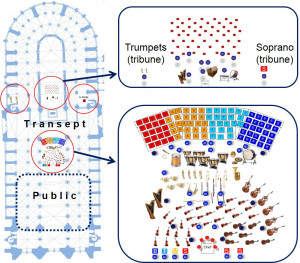

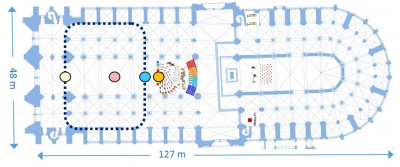

On 24-April-2013, a grand concert was organized in the Notre-Dame cathedral, to celebrate its 850th anniversary. A symphonic orchestra, 2 choirs, and 7 soloists performed “La Vierge”, composed by Jules Massenet in 1880. The following image depicts the placement of the instruments and section microphones during the concert. Each instrument section and soloist were recorded using a total of 44 microphones in close proximity. As the direct-to-reverberant ratio is high for close mic recordings, these were employed as approaching anechoic recordings for the purpose of the virtual concert.

Full details of the recording setup have been assembled in the following Report (in French).

Acoustic simulation & Auralization

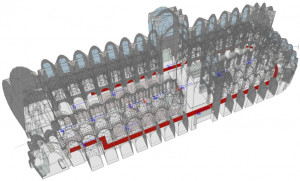

A computer room acoustic model of the Notre-Dame cathedral was created, as shown below. The geometry of the Notre-Dame cathedral was determined from a 3D laser scan point cloud and architectural plans & sections. To each element of the model was assigned a specific acoustic material, related to the acoustic absorption and scattering properties, representative of the surface's roughness. This geometrical acoustics model was then fine-tuned through calibration to match the acoustic parameters obtained from measurements.

With the calibrated model, each soloist and section of the orchestra was defined in the model, with the corresponding directivity patterns. Virtual listener locations were then defined, and the acoustic propagation characteristics of the cathedral, for each source-receiver combination, were calculated, a process taking several weeks. This calculation produces what is termed the Room Impulse Response (RIR) for each source-receiver combination.

With these RIR results, which are represented as signal filters, each recorded track is processed with the corresponding filter, thereby placing the recorded performance in the virtual room simulation, a process called auralization as the audio parallel to visualization.

Details of this procedure can be found in this article : VR Performance Auralization in a Calibrated Model of Notre-Dame Cathedral.

Mixing / Post-processing

While the recorded tracks can be auralized using the computer model simulation results, the relative levels and balance between the recorded tracks need to be adjusted to account for the microphone and recording conditions. These adjustments by the recording engineer are made to provide the most realistic result, based on listening to recordings made a several positions in the cathedral during the concert.

This mixing is not based on the usual approach (assuring the precision and clarity of the restitution of the different instruments and singers), but on a realistic restitution of a listening sensation in-situ, such as one could have in these different positions in the Cathedral on the day of the concert.

Limitations

There are many limitations to this production, be them technical or due to available time. Some of the most pertinent limitations are discussed below.

While a significant effort was made to get close proximity recording of all performers, this was not always possible. In such instances, like the procession of the children's choir, ambiance recordings were used instead of proximity recordings. As these ambiance include the room acoustics, they are not processed through the virtual acoustic model, as this would produce a double reverberation effect. To integrate these elements into the virtual concert, they have been binaurally rendered, placing them at the approximate positions during the performance.

Due to the imperfect recording conditions of the concert, some microphones pick up extra instruments at times, which requires fine adjustments to remove them when possible. When both instruments are playing, this cross-talk between recorded tracks can not be corrected. The results is that at times some instruments may appear to come from multiple positions within the orchestra, somewhat blurring the spatial precision of the virtual concert. In addition, there are a few moments when musicians may have slightly bumped the microphones, or rustled their scores, which of course gets included in the production.

In virtual acoustic renderings, the goal is to recreate the spatial acoustic cues that we as humans use to “decode” the soundscape around us. Such cues are represented by what is termed the Head-Related Transfer Function (HRTF), and like the RIR of the cathedral, it is specific to the geometry, here being an individuals head, torso, and especially ear shape. As it was not possible to render this concert performance individually for every listener, it was necessary to choose the HRTF, or the “ears”, of an individual which we all will listen through. As a subject of active study by the acoustic research team, numerous listening tests have been carried out previously comparing how we hear through other people's ears. For this project, we selected the most often best rated set of ears from our most recent study. This was the HRTF number 1032 from LISTEN HRTF database, by IRCAM. For the cases when ambiance recordings were spatialized directly through binaural processing, the same HRTF was used to assure spatial perception coherence.

An alternative would be to rely on dynamic decoding over headphones, which was previously used for an audio-visual virtual fly-through of the cathedral, with only a short extract of the concert. While the spatial precision of this real-time VR presentation is currently not as high (due to streaming limitations) as the methods used for this concert, the ability to move your head (best when using a smartphone with gyroscope tracking) really benefits immersion in the virtual cathedral.

As a final point, we would like to indicate that part of the simulation work, and the entirety of the mixing and creation of this website, was carried out during the COVID-19 confinement period in France, working on mostly portable and home machines, with all their limitations.

Project Background

This work is an extension of the original Ghost Orchestra production (2013-2017) funded in part by the FUI-BiLi project on Binaural Listening and the ANR-ECHO project concerning Digital Heritage and Historic Auralizations.

This earlier project resulted in a short excerpt of the “La Vierge” concert with a virtual reality 360° video with spatial audio and an orchestra fly-over and tour of the virtual cathedral (simplified visuals, as this is an acoustic project). An update of the graphics has been made in 2020 thanks to better available rendering capabilities.

Best results are achieved using a smartphone or tablet with gyroscope tracking. Most importantly, don't forget to wear headphones.

Principal Contributors

- Concert recording supervisor / Audio Engineer - Jean-Marc Lyzwa (CNSMDP)

- Project manager - Brian F.G. Katz (Sorbonne Université)

- Graphics, final integration, & project coordination - David Poirier-Quinot (Sorbonne Université)

- Geometrical acoustic model - Bart Postma & Julie Meyer (LIMSI)

- Assistant Recording engineers - Pierre Blaise, Etienne Caylou, Thibaut Lalanne, Yoann Saunier (CNSMDP)

Acknowledgements

- The team would like to thank the Rector-Priest of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, Monsignor Patrick Chauvet, for the authorization he granted to us for these recordings and measurements.

- This effort has been made possible by a grant from the CNRS Mission for Cross-disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Initiatives (MITI) and the Acoustic & Soundscape task force of scientists, “Chantier CNRS Notre-Dame”.

- This production would not have been possible without the performers and musicians:

- Maîtrise Notre-Dame de Paris, Lionel Sow, chef de chœur

- Chœur de l’Armée française, Aurore Tillac, chef de chœur

- Chœur d’Enfants Sotto Voce, Scott Alan Prouty, chef de chœur

- Orchestre du Conservatoire de Paris, Quentin Hindley, chef assistant

- Laura Holm, soprano; Charlotte Desaux, soprano; Caroline Michaud, mezzo; Benjamin Woh, ténor; Samuel Hasselhorn, baryton; Norah Amsellem, soprano

- Patrick Fournillier, direction

Tools

- Geometrical Acoustic simulations - All acoustical calculations were carried out using CATT-Acoustic™ v9/TUCT2

- Visuals were rendered in Blender

- Audio convolutions with the simulated room responses were achieved using the SPARTA VST-plugin suite from Aalto University, Finland.

- Binaural spatialisation of ambient tracks were achieved using the Anaglyph binaural spatialization engine from Sorbonne Université, France.

Links

- Ghost Orchestra project

- ANR-ECHO project

- FUI-BiLi project : Binaural Listening

- Introduction to room acoustics and auralizations, from the ECHO project

- EVAA : Experimental Virtual Archaeological-Acoustics research

Contact

If you have any question or comments, please contact brian.katz@sorbonne-universite.fr.